| |

“A magnificent desolation.”

Edwin Aldrin, Apollo 11,

July 1969

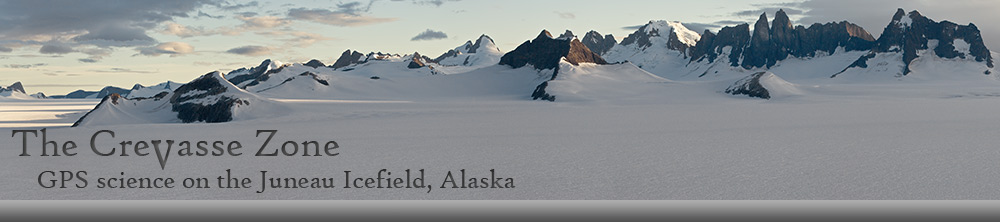

Although spoken from the surface

of the Moon, Edwin Aldrin’s words perfectly capture the essence

and experience of the Juneau Icefield. Stretching 90 miles from

Juneau, Alaska north to Skagway, the Juneau Icefield is one of

the world’s largest non-polar masses of snow and ice. Though

seemingly remote and inhospitable, its close proximity to

Alaska’s capital city draws tourists, adventurers, students, and

scientists to its lush, rain-forest-rimmed perimeter and its

barren interior.

Seven decades ago, it was the

interior of the Icefield that attracted the attention of a

young, energetic glaciologist named Maynard Malcolm Miller. As a

member of the U.S. Navy during WWII, he was involved in several

projects examining the impact of weather and climate on military

operations, particularly in the north polar region. In the early

1940’s, and throughout WWII, there was much interest in using

the polar ice cap as a base for military operations. But to do

so, it was necessary to understand the role of both short-term

weather and long-term climate on the formation and stability of

the polar ice pack. Unfortunately, the dynamic nature of the

polar ice pack retained a record of only relatively short-term

weather events. A longer annual record of weather and climate

was needed. Thus it was necessary to find a location where

long-term climate changes could be observed.

Recognizing that glaciers record

hundreds, or even thousands of years of climate events, in 1946

Maynard lead a small group of explorers on a reconnaissance of

the Juneau Icefield to investigate its potential for climate

research and the feasibility of establishing a long-term

glaciological research program. Thus began one of the longest

continuous-running programs of its kind in the world. Dedicated

to education and science, and now it its 63rd year, the Juneau

Icefield Research Program (JIRP) continues to attract students

and scientists from around the world.

The program’s success lies

partly in its approach to education - learning from Nature, in

Nature. This is also the key point of the Emersonian Triangle.

In his 1837 oration, The American Scholar, Ralph Waldo

Emerson enunciated the three primary influences on scholarly

development and effectiveness: Nature, Books, and Action. He

proposed that Nature is the ultimate arbiter of truth, the

source from which knowledge is obtained. Books are the

transcript of other men’s accumulated knowledge of Nature. And

he believed Action is required of the scholar to investigate

Nature, adding to the body of knowledge.

This philosophy is embodied in

the Juneau Icefield Research Program. During their two months

living on, researching, and traversing the Juneau Icefield,

JIRP’s students and scientists are immersed in Nature. They

learn from Nature that the Icefield is more than just snow, ice,

and rock. They learn it is an integrated, synergistic system of

disparate elements acting together to provide clues to, and

evidence of, past climate. They learn Nature has a story to

tell, and they learn how to decode the secrets of Nature.

|

|

A

A

One of the key goals of the Juneau Icefield Research Program is

to impress upon its students the importance of the Emersonian

Triangle, and to continue its long legacy of percipio quo

Natura, in Natura (to learn from Nature, in Nature). And

what better place to do this than the magnificent desolation of

the Juneau Icefield.

Life on the Icefield

JIRP's annual field season runs from early June to early August. During

this time, all participants hike and ski 80 miles across the

Icefield from Juneau, Alaska to the shore of Atlin Lake in

British Columbia. A 40-mile boat ride completes the traverse to

the town of Atlin.

The first five days of the

program are spent in Juneau for orientation, field trips, and

academic lectures. Participants then hike up to Camp 17, the

first of several permanent camps maintained by JIRP.

Participants spend a week at Camp 17 for glacier safety

training, ski practice, and introductory lectures. A two-day ski

trip then takes everyone to Camp 10, the main camp in the middle

of the Juneau Icefield. The next several weeks are spent on

field work, lectures, and moving from camp to camp northward

across the Icefield. This is a full immersion program - there

are no days off and no trips out to Juneau.

A typical day begins at 7:00

wake-up, followed by breakfast, daily announcements, and camp

maintenance duties. Field trips, project work, and lectures

round out the day, with lights out at 11:00 pm. Students are

involved in various research projects, ranging from geology,

mass balance, meteorology, botany, geophysics, and GPS

surveying. Students also have the option to define their own

research project, in collaboration with faculty and staff

members.

Participants begin making their

way off the Icefield around August 12-15 with a ski trip to Camp

26 on the Llewellyn Glacier. Several days later they are picked

up by boat on the shore of Atlin Lake for the trip to Atlin.

There, the program wraps up with final lectures, field trips,

and student presentations of their research projects. Students

then travel by bus and ferry back to Juneau for their flights

home.

For More Information

To obtain more

information about the Juneau Icefield Research Program, visit

the JIRP Web site or write to the address listed below.

Juneau Icefield Research Program

4616 25th Avenue NE, Suite 302

Seattle, WA 98105

USA

E-mail:

fger.jirp@juneauicefield.org

Website:

http://www.juneauicefield.org

|

|